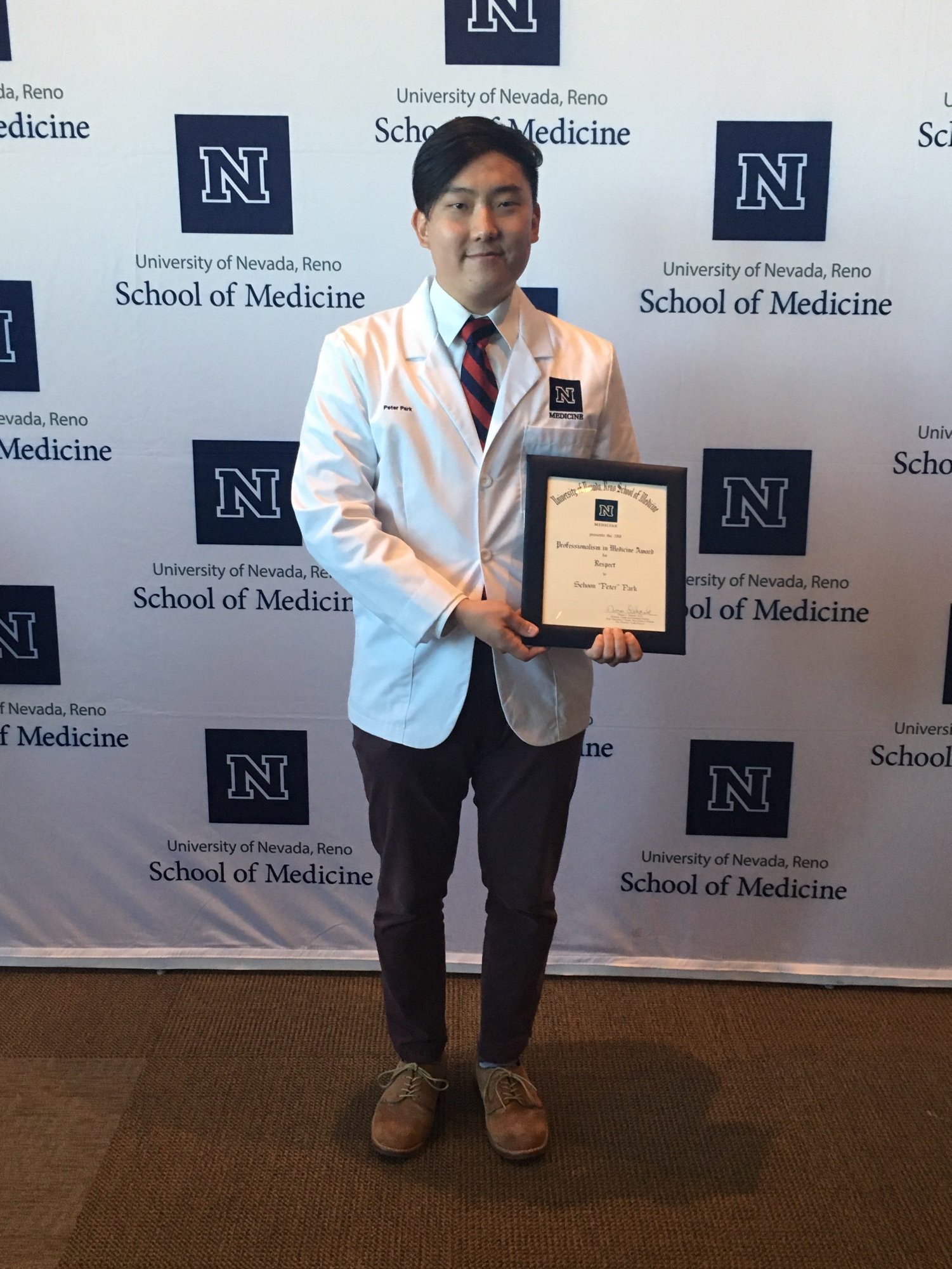

Although Peter Park, a graduating medical student and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient has been limited to what kind of work he can do in a clinical setting, he has still found ways to contribute during the coronavirus pandemic.

Park volunteers with the Regional Emergency Medical Services Authority (REMSA) screening COVID-19 phone calls and helps triage potential screening candidates. This July, the 28-year-old Park starts his five-year residency program in Las Vegas, Nevada, where he could potentially take care of patients with the novel coronavirus. Then, after a fellowship program and years of hard work, Park would finally achieve his dream of becoming an orthopedic surgeon.

But these plans could soon change entirely. Park, along with more than 600,000 other DACA recipients nationwide, anxiously await the ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court who, any day now, will decide their futures in the country they’ve call home since childhood. If the highest court in the land sides with the Trump Administration – who attempted to end the Obama-era government policy since 2017 – Park and other DACA recipients could no longer legally reside or work in the U.S.

And yet still, a great number of those with DACA status are in positions now considered essential because of the coronavirus pandemic like teachers, medical professionals, and food-related workers.

For people like Park, the repeal of DACA would be life-changing.

He and his family first arrived in the U.S. from Seoul, South Korea when he was nine years old. Originally on a tourist visa, due to a set of unfortunate circumstances, they ended up overstaying.

“We hired a lawyer to help us renew our visa, but he took advantage of our situation and took the money and ghosted us,” Park said. “My mom felt there wasn’t a great future for us back in Korea so I think that is when she decided to overstay the visa instead of returning.”

As Park got older, he dreamt of working in medicine. Whenever he would volunteer at the hospital, he knew this was the field he wanted to go into. He wanted to help people.

“To repeal DACA at this time would not only hurt the patients, but the hospitals [as well].”

— 28-year-old UNR Medical Student Peter Park

But, as an undocumented citizen, it wasn’t possible for him to apply to medical school. It wasn’t until DACA was finally created in 2012 that Park could pursue his dream.

“It was very important to me,” Park said. “I remember being elated when I got the status.”

Since then, Park has worked to succeed in his field. He received a full scholarship to attend the medical school at the University of Nevada, Reno, He regularly placed at the top of his class and according to him, spent much time and energy striving to be his best. He said it would be devastating for him and the general public for DACA to go away right now.

“In all levels of healthcare, we have [DACA recipients],” he said. “To repeal DACA at this time would not only hurt the patients, but the hospitals [as well].”

Park is a part of the subset of 29,000 healthcare workers with DACA status in the U.S., according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. He stressed that getting rid of DACA wouldn’t be good, but doing it right now would be even worse.

“Whatever your stance is on DACA, this is just a really bad time to do it,” Park said. “We’re in a crisis. We need all hands on deck.” –CC