Cachanillas in Reno: From Mexicali to Reno’s High Desert

June 26, 2018 By

Lisette Gallarzo Guerrero

Mexicali, Baja California, is a desert valley on the U.S.-Mexican border. Its population of about one million people identify themselves as Cachanillas, or Mexicali natives.

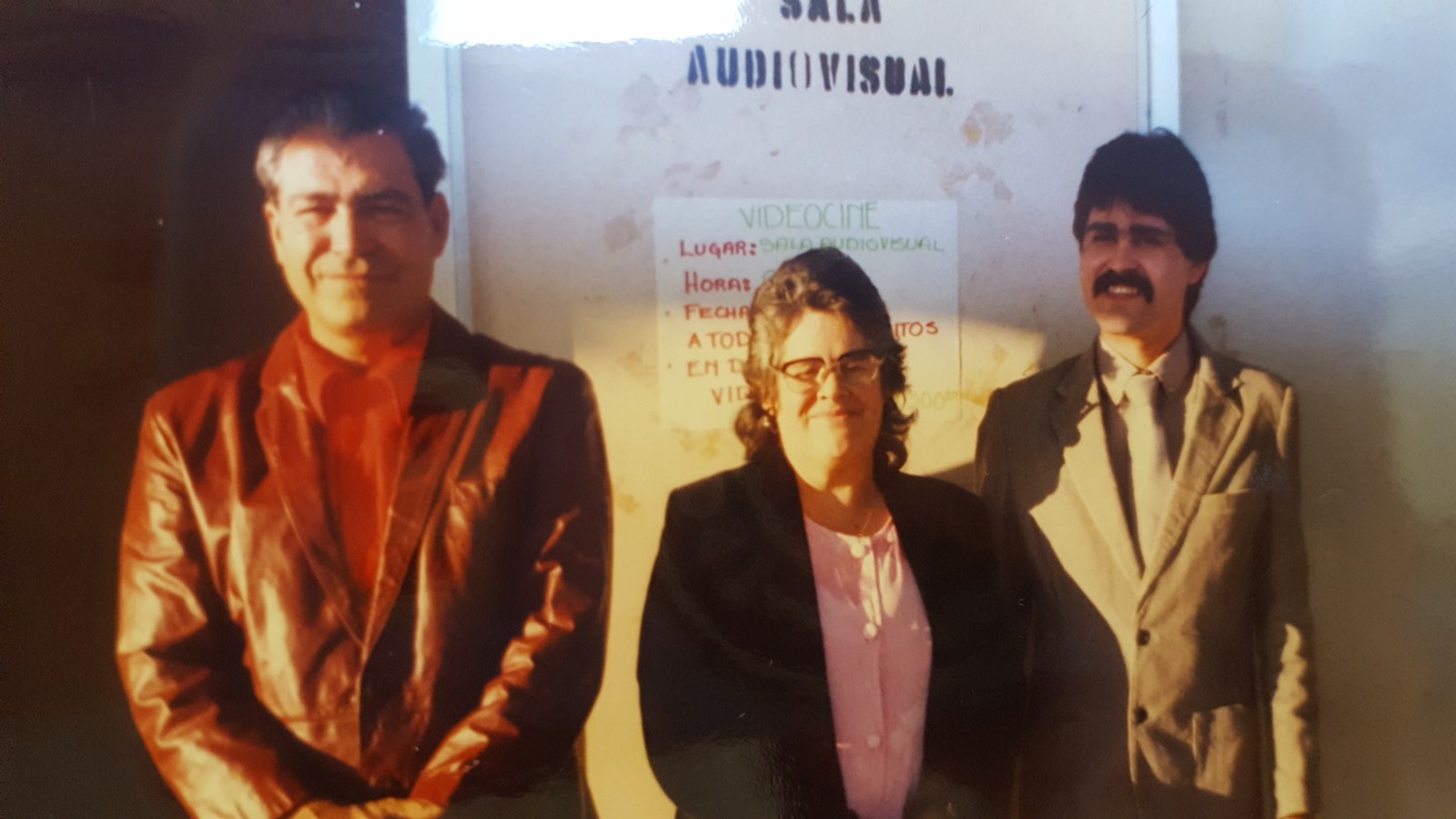

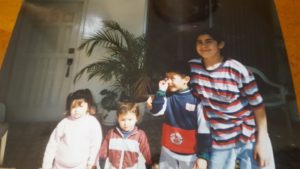

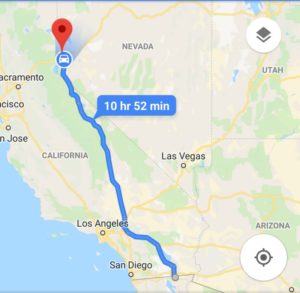

In 1978, my grandfather José Orozco migrated from Mexicali, Baja California’s capital city, to Reno, Nev. As he prepared to head for California’s agricultural fields originally, a friend of his tipped him off to the work to be found in the Biggest Little City’s casinos. My grandfather brought along a few of his children, including my father, while he worked for four years in Reno before returning to Mexicali. My dad received his high school education from Hug High School and years later, after receiving his civil engineering degree from Mexicali’s university UABC, he returned to Reno with my mother and my then three-year-old brother. About six years later, I was born in Reno but my earliest memories are divided between both cities.

In the past year, I’ve connected with peers whose own roots take them back to Mexicali, too.

Varied Connections

Leslie Escalera-Nuñez is a 21-year-old undergraduate student at the University of Nevada, Reno, originally from the Las Vegas area. Her mother, Andrea Smaltino, was born and raised in Mexicali before moving to Las Vegas when she was about 10-years-old. Although Escalera-Nuñez visited Mexicali often during her childhood, as she grew older, those trips became more and more infrequent, making her connection to her mother’s hometown feel increasingly strained.

“Honestly I don’t feel very connected because I’ve only gone to visit for short amounts of time — maybe if I had been there longer periods or really spoke Spanish really well maybe I would feel a little more connected, but neither of those are true, so it’s kind of hard to really relate, especially since I have only lived here, in the United States, so it’s kind of hard to justify that,” said Escalera-Nuñez.

Alejandra Hernández Chávez was born in Mexicali’s local and public hospital in February of 1994. Hernández Chávez and her family migrated to the United States five years later in 1999 when she and her younger sister entered the U.S. on a one-day visa on a trip to Disneyland. The young girls overstayed their visas until they were able to receive their American citizenship years later.

It would be nine years before Hernández Chávez would return to her hometown, a visit she feared at the time.

There wasn’t a great recollection of like, ‘Oh yeah, I’m going to go see this or I’m going to get to see this person,’ because it was such an abstract, far away idea. I knew where I was from, but I didn’t know the place. I didn’t remember anything. I had no attachment to it and you know, you grow up with this western idea of what Mexico is and what it looks like and the crime and all this,” said Hernández Chávez.

She was surprised by a deep resonance upon returning.

“To have that connection with people who have my accent, who understand my slang, who only taught me more about my area and my history and to really feel the connection just when we’d literally had just driven through and it was like, ‘Okay, you’re on the side of this side of the border now.’ It was powerful and like I said, I’ve not felt it with any other place. And I think it’s just that missing key of our bodies and our energies knowing where we’re from and not having it for awhile and it was just like, ‘It’s here, it’s, there, it exists,’” said Hernández Chávez.

I’ve always felt a strong connection and resonance to Mexicali because, during my visits, I recognized my parents in the language, in their stories and memories of the city, and I have so much family to welcome me home that it feels difficult not to feel like I have a place there. My grandparents have lived in the same homes since I was a little girl, and I have made just as many significant memories in those homes as I have in the homes I’ve lived in in Reno. I have memories as far back as opening presents on Christmas when I was five-years-old in my nana’s house in Mexicali, to having my quinceñera in my parent’s favorite church, to memories as recent as attending my tata’s, or grandfather’s, funeral at a local cemetery there last year. Mexicali undeniably holds too many pieces of myself and my family’s past to be insignificant.

A Bicultural Identity

When Escalera-Nuñez reflects on how Mexicali has influenced her own personal identity, she says that her bicultural background has shifted her perspective.

“I think I value and appreciate certain things a little bit more than people who are from here. I feel like because I have seen places more in poverty and people who struggle a lot to have just a little bit, and here, people have grown up a little bit more privileged, but I think I just appreciate things a lot more,” said Escalera-Nuñez.

Throughout Mexico, people from the Northern states are identified as Norteño/as and their identities are known to have “American tendencies,” like a Spanish-language that has closer similarities to English than in Mexico’s southern states.

Hernández Chávez mentions that she identifies with the difference between not only being a Norteña but also as being from a town right on the border.

Having to deal with how Western my identity is because of my proximity to America but also the time I spent in America, and also how American a northern state tries to be because they really do. Mexicali picks up a lot of tendencies from the U.S. because you’re so close — so that difference being not only a Norteña but a frontera, being right on that line,” said Hernández Chávez.

Being from la frontera, or the border, has had a profound influence on my own personal identity. As a first-generation American, my identity has been incredibly flexible and adaptable, but it has also blurred the boundaries of a physical border, making it challenging to strongly identify and feel belonging with one place, one country, or one culture.

My identity provides me with the great privilege of travelling back and forth between the U.S. and any Latin American country and adapting a bit quicker to the language and cultures than others might. However, it also means that I’m not seen as a “native” in either country. Both American and Mexican citizens recognize me as a foreigner and my place of “belonging” is abstract, at best.

My bicultural experience has definitely been an influence in choosing my own academic career as a journalism and Spanish dual-major. While personal strengths and interests of mine, such as writing and meeting and connecting with new people, are the reason I want to be in a communication field, my cultural background and knowledge of the lack of representation for Latino communities fuels my passion to be a reporter. I hope to contribute to Latino communities everywhere as a bilingual journalist by sharing their stories and voices in any way I am able to. My goal is to create a more holistic and authentic perception of a community that is largely stereotyped and marginalized.

As women whose roots pass through Mexicali but are currently planted in Reno, could our post-graduate career paths lead us back someday?

Hernández Chávez has a tattoo of a monarch butterfly on her forearm, and explains, “People use monarch butterflies a lot to represent the immigration, but also monarch butterflies come from Mexico and then their cycle takes them up to Canada, but then they eventually come back, and I tell people that I always hope my cycle takes me someday back to Mexico,” said Hernández Chávez.