Just a year before his death, actor Matthew Perry said that he wanted to be remembered not only for playing Chandler Bing on “Friends,” but first and foremost for how he helped people overcome their addictions. Having witnessed the world’s response to the actor’s untimely death, of course, the opposite turned out to be true. Many mourned not only Perry, but the joy he brought them as Chandler. Matthew Perry will perhaps always be remembered primarily for his role as the sarcastic and lovable Chandler Bing, and secondarily as the person behind the character. Such is the case for many an actor, in both life and death.

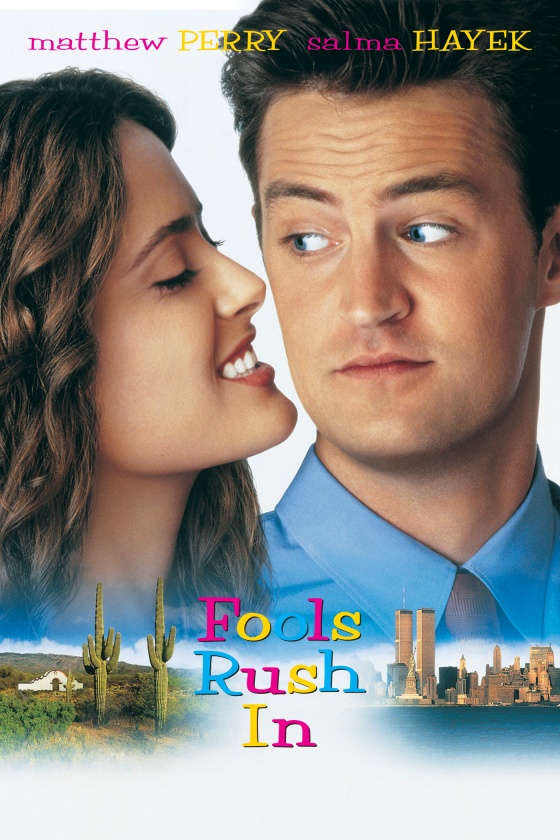

This has been the case since the star broke out into his first lead film role in “Fools Rush In,” a romantic comedy set in Las Vegas, Nevada, starring Salma Hayek about an intercultural couple navigating their unconventional route to love through their cultural differences. Matthew Perry plays Alex Whitman, a WASPy and witty businessman who works for a firm that builds nightclubs, which is how he finds himself in Las Vegas and meets Salma Hayek’s character Isabel Fuentes, a talented Mexican-American photographer who takes desert landscape photos.

Despite its profits, though, the film wasn’t critically well-received. However, contrary to what the critics say, “Fools Rush In” isn’t just a silly and cliched “opposites attract” romantic comedy. This film has a lot of cultural commentary, and despite some of its more tropic moments, it ultimately represents aspects of Latinidad in a respectful and culturally-aware way. Reducing this movie to just another romcom is simply foolish, and it stops conversation about important moments of cultural awareness (and unawareness) of Latinos in this film from happening.

Several moments in this film capture real-life patterns that have been observed by scholars of the idea of Latinidad, which is basically the essence of what makes Latinos, Latinos. Some of these patterns include the concepts of familismo and religiosity, two major themes in the film. “Fools Rush In” also explicitly addresses Latino stereotypes in the media by using uncomfortable moments between the white and Mexican characters to debunk these stereotypes.

In media scholar Frances Negrón-Muntaner’s “The Latino Media Gap: a Report on the State of Latinos in U.S. Media,” one of the main conclusions was that “stereotypes restrict opportunities and perceptions.” Negrón-Muntaner notes how portrayals of Latinos in media primarily depict them as three things: criminals, law enforcement and low-wage workers. “Fools Rush In” doesn’t fall into this trap. Instead, it depicts the lead Latina character as an individual: Fuentes is a professional who photographs the desert and casinos.

The movie goes one step further than simply representing a Latina character with a non-stereotypical job. It explicitly addresses how repeated portrayal of Latinos in media as low-wage workers affects the perception of Latinos by other groups. In one scene, Whitman’s parents unexpectedly appear at his temporary home in Vegas, and they encounter Fuentes. Not knowing that she is Alex’s wife, they assume she cleans his house. “Now that is what I call a housekeeper,” says his father, simultaneously objectifying Fuentes and assuming her class within a matter of three seconds.

This cringey moment lays bare the power of stereotypes, that they prevent people from seeing others for who they truly are. A 1997 movie review from the Hamilton Spectator by Jim Bray even noted that “the filmmakers don’t stereotype hispanics for the sake of laughs.” Nor do the filmmakers stereotype Hispanics for the sake of lazy writing, either.

“Fools Rush In” gets most of its criticism for other aspects of its writing, which many of its original critics found predictable, lazy or cliché. To its credit, though, it wasn’t meant to be a groundbreaking cinematic masterpiece — it’s a romantic comedy, which are often exactly the opposite of what many would consider groundbreaking cinematic masterpieces. The very genre itself requires that the viewer watch it while already knowing what’s going to happen: that the two protagonists, despite their conflict (and there is always so much conflict), will end up together in the end.

This doesn’t mean that these films aren’t valuable lenses into culture, though. Romantic comedies are enjoyable because of how the two main characters end up together, and not merely because they end up together. Furthermore, the conflict in the romantic comedy is also where we can start to read how culture as the central conflict in “Fools Rush In” is significant to the plot.

The central tension of “Fools Rush In” revolves around how the cultures of the two main characters’ families clash. John Petrakis from the Chicago Tribune cheekily illustrates some of these parallel (though admittedly clichéd) when he writes that: “[Whitman’s] family is cold and WASPy, hers is warm and Catholic.” Though this representation is perhaps a bit shallow and superficial because it reflects society’s overall ideas of what Mexican and Protestant families look like, the film does get some things right by representing, in scholar Kristin C. Moran’s words, the “attentiveness to extended family members (familismo) as well as their desire to please elders by showing respect (respeto)” that Fuentes has for her family.

For example, in a scene where Whitman meets Fuentes’ family at dinner (so that when she tells her family she’s pregnant, she can at least say that her family has met the father before), he says “I had no idea that families actually talked at dinner.” This idea of the cold Anglo vs. the warm Mexican family is woven throughout the film. In many ways, this depiction of the cultural traits that society associates with different families doesn’t do anything very different or groundbreaking, staying well within the lines of the status quo. However, it does reflect the close-knit structure of many Mexican families.

Despite its shortcomings, according to famed film critic Roger Ebert’s 1997 review of the film, “there is also a level of observation and human comedy here; the movie sees how its two cultures are different and yet share so many of the same values, and in Perry and Hayek it finds a chemistry that isn’t immediately apparent.” Much of the actual romance in the film centers around how the two main characters’ values align, indicating that perhaps it is their differences that make them similar.

Though this film misses opportunities to make deeper critiques of how society views cultural differences, this film does give us a unique and somewhat-refreshing portrayal of a Latina in a romantic comedy, a genre that is all-too-tempted to write Latinas into ethically-suspect storylines that revolve around maids falling in love with their bosses. It also gives us two significant and memorable performances by both Perry and Hayek, which were some of their first breakout roles in a major motion picture in the US. Despite the overall positive portrayal by the media of Mexican families as beacons of warmth, amazing food, and connection, this single portrayal can get repetitive and reductive. To quote Ebert again, “someday we will get excitable WASPs and dour Mexicans, but not yet.” Until then, we can analyze the films and media that already exist, and begin to tell the real stories that don’t yet exist in the eyes of the media.

Lola Works is a student in the Reynolds School of Journalism at the University of Nevada, Reno. She contributed this opinion-editorial to Noticiero Móvil.

This commentary is part of the “Latinos in the Eyes of the Media” special series. In this section, Noticiero Móvil publishes pieces by UNR students that dive into films and television shows in which Latino characters, culture and norms are portrayed. The goal is to explore and illuminate how a lack of Latino representation in the media continues to promote some of the discriminatory and stereotypical practices that affect Latinos to this day in the U.S.