With a body at war with itself cancer not only invaded Aimee Naomi Arrellano, but also hid from her.

Raised in Reno, Nev., Arrellano never planned to be a fighter, but life didn’t leave her a path without obstacles. That is why college was not the most obvious next step for her. Instead, it was a distant dream.

“I didn’t feel like I had any other options,” she said. “I didn’t grow up with people who went to college, so I’m the first in my family.”

The young woman found her way to the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR), majoring in journalism and communications, with a focus on news and broadcast. This world excited her because of the idea of being able to tell stories and have an impact. But just as her dreams began taking shape, the book of her life turned to a chapter she never expected.

It all started quietly, imperceptibly, with a mild itch that was more bothersome than anything else. The rash did not go away. On the contrary, it grew, spreading across her body and burning beneath her skin. During her sophomore year of college in 2022, Arrellano was supposed to be making memories with friends and starting to build her future. Instead, she found herself trapped in a cycle of constant discomfort.

“I was switching products. Avoiding perfumes, switching soaps,” Arrellano said. “I went to allergists, dermatologists, even my primary care physician. They told me it was ‘probably the dry Nevada air’ or that it was ‘some product I was using.’ But nothing worked,” she recalled.

Doctors prescribed her allergy pills — not just one, but three different ones every day. She tried steroids, anti-anxiety medications, and even sleeping pills when the itching kept her awake. Nothing improved her situation. Her life became a constant guessing game, trying to avoid triggers she did not even understand.

“I was constantly thinking about it,” she said. “It wasn’t just an itch; it was a prison. I could not concentrate in class, I didn’t want to go out, and every time I looked in the mirror, I felt like I was losing control of my own body.”

Beyond the itch being a nuisance—it was a warning, a silent alarm her body was trying to sound. But no one seemed to be able to hear it.

In March 2024, Arrellano experienced another symptom: a deep, wet cough that refused to go away. At first, she thought it was another cold, but this was different. The cough was thick, sometimes tinged with blood.

When Arrellano mentioned the cough during a routine checkup, they ordered an X-ray as a precaution. She did not pay much attention because she was used to doctors finding nothing.

This time, they found something: a shadow on her chest. As a follow-up, they sent her for a CT scan. And while she waited for the results, Arrellano noticed the formation of a lump in her neck. It was then that the fear began to set in.

“I remember trying to prepare myself mentally,” she said. “Like, deep down, I knew it was cancer. Why do they keep sending me for more tests?”

A biopsy of the lump proved inconclusive, but a PET scan revealed the truth: Stage 2 Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer.

According to the National Foundation for College Students with Cancer, 89,000 people between the ages of 15 and 39 are diagnosed with this disease each year. One in every 100 college students is a cancer survivor. Locally, the organization My Hometown Heroes offers resources and scholarships to UNR students with cancer, as few programs focus on young people of this age with cancer.

Despite the news, at the time, Arrellano felt relief.

“Finally, someone knew what was happening to me,” she said. “But it was the worst response I could have imagined.”

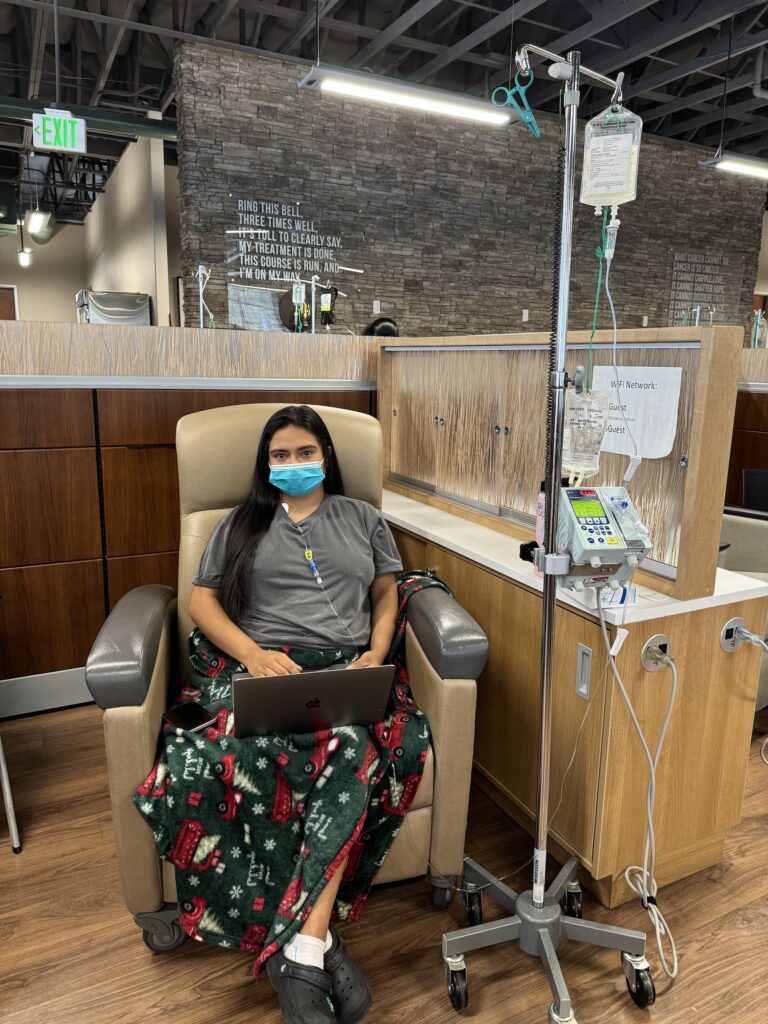

Doctors told her it was a “good” type of cancer to have, Hodgkin lymphoma, as it was highly curable. So, Arellano did not feel lucky but scared. Her life turned upside down overnight, and college took a backseat. Instead of studying for exams, she prepared for chemotherapy, 12 grueling sessions.

“I started chemotherapy on August 1, 2024,” she recalls. “I tried to stay positive. People said, ‘You’re strong. You will make it through this.’ But they were not the ones losing their hair; their bodies weakening.”

The first sessions were a nightmare — nausea, fatigue, a constant ache that settled into her bones. But the worst part was the waiting. Waiting for her body to respond. Waiting for her chemotherapy to show that the poison was working.

By the eighth session, the cancer was still there. Resistant. Relentless. Her doctors contacted specialists at the University of California, San Francisco, desperate for a new plan. That is when they introduced immunotherapy, a treatment that would not only poison the cancer, but also train Arrellano’s immune system to attack it.

“I thought, maybe that worked. Maybe this is the solution,” she said.

But the side effects would be terrifying. Immunotherapy could cause her immune system to attack healthy organs. Arrellano was forced to sign consent forms warning of potentially life-threatening complications. But at that point, she had no choice. It was a risk she had to take.

And although immunotherapy helped, it was not enough. Her medical team recommended a bone marrow transplant, a last resort. The plan was set. She would travel to San Francisco in May 2025, spending at least a month and a half there, undergoing high-dose chemotherapy and the transplant.

For Arrellano, cancer hasn’t just been a battle with the disease; it has been a fight for her sense of identity. College, once her refuge, became a source of pain. Watching her friends graduate, move on, and achieve their dreams is like watching her life pass her by.

“I had one semester left. Just one,” she said, her voice breaking. “And instead, I was trapped. I felt like I was falling behind.”

But as much as cancer has taken from her, it has also shown her who she is. It had taught her to fight, even when the fight seemed impossible. Moreover, it has revealed the pitfalls of a healthcare system that almost let her die.

Arellano is more than a survivor. She is a fighter, a student, and a young woman who refuses to be defined by her illness. One day, she will sit in front of a camera, sharing the stories of others. And when she does, she will know better than anyone how much strength it takes to make her voice heard.