No name is more synonymous with the Comstock Lode than John Mackey. Hard-working and industrious, Mackey became fabulously wealthy from the legendary silver of the Comstock, and developed a mythos of his own in the history of Nevada. Mackey’s legacy as a miner and a philanthropist is so great that every year students at the University of Nevada, Reno, provide tributes of liquor bottles to a statue of him during finals week.

Yet, before he struck it rich, Mackey was just a miner and (perhaps) a carpenter working at one of the Comstock Lode’s earliest success stories: the Mexican Mine.

The legacy of the Comstock Lode is widely known in Nevada, but the stories of the Latino miners who helped lay the groundwork for the region’s success is not. However, extended research into the history of the Latinos of the Comstock being performed and presented by the Shared History Program in the College of Liberal Arts is starting to shed light into their role in the Comstock’s history.

Read in Spanish: La vida y el legado de los mineros latinos de Comstock

Early Success and the foundation for riches

The Comstock Lode is one of the richest silver deposits in history, turning miners into billionaires and funding the development of places like Nevada and San Francisco. Mackey’s Consolidated Virginia Mining Co. extracted ore worth around $2.3 billion in today’s dollars from 1873 to 1882. Yet, early success was not a given at the Comstock Lode, and the technical expertise needed to make it profitable to mine silver came from Latino Miners.

“[Virginia City] is a cauldron of new techniques and technologies,” said Dr. Christopher von Nagy, the head of the Shared History Program at the University of Nevada, Reno, “but it is being built on the fundamentals of Latin American mining.”

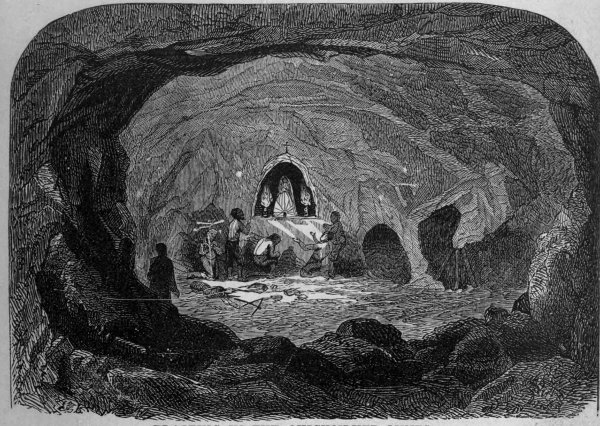

Early miners in the region had no experience mining silver, and did not know how to separate it from the surrounding metals. Latino Miners crossing over from California were well versed in a centuries-old silver milling process called the patio process which made it possible to extract the pure silver from the mineral deposits of the Comstock. Using heavy stone wheels called arrastras, sunlight, mercury, and adobe furnaces, Comstock miners made use of a slow but profitable Latin American mining technique.

“Without using the patio process, why go to Virginia City? They started producing gold and producing silver and people were like, ‘hmm, okay’,” said von Nagy.

While the patio process was too slow to be sustainable, being able to make any profit at all allowed Virginia City to develop into a mining hub. When the technologically superior Washoe process of milling silver was developed, it was based on the foundations of the patio process brought by Latino miners.

“Once you have a lot of people and there’s this desire to push production, people start experimenting with innovations to the patio process,” said Von Nagy.

“If it wasn’t for the Latino miners coming up and showing the Anglo-miners this process, they would not have had the capability of pulling the material out of the ground to nearly the extent they needed to draw a population,” said Associate Guest Curator of the Latino Miners exhibit DT Burns. “By drawing that population we were able to get a population high enough to get [Nevada] into territory and statehood.”

The legendary and mysterious Maldonado Brothers

In the early period of the Comstock, Latino miners not only lended their knowledge to the operations of others, but also found success themselves.

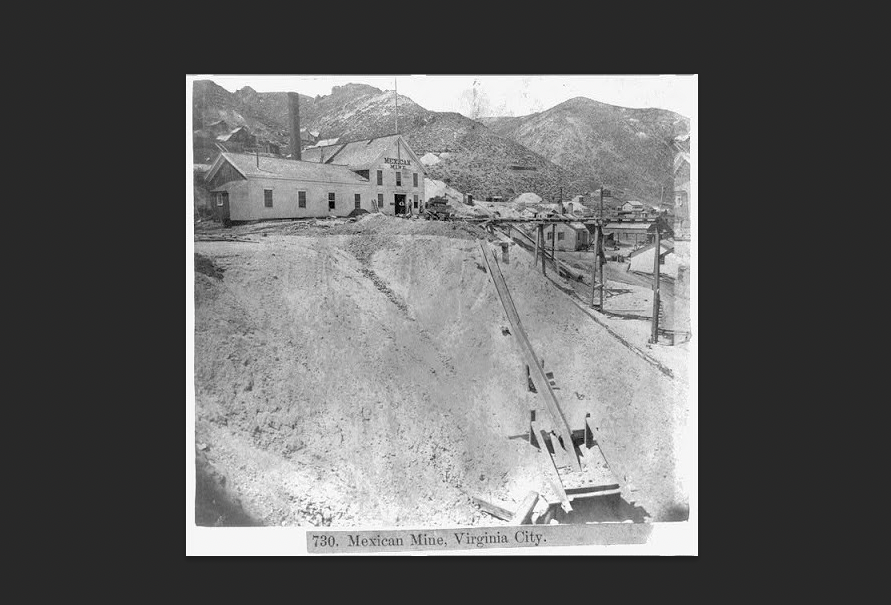

Of particular note are the Maldonado Brothers, Gabriel and Francisco, who owned the Mexican Mine at the Ophir bonanza of the Comstock. Very little is known about the brothers, but the knowledge that does exist suggests they were some of the most important and influential early Comstock figures.

“Two brothers named the Maldonado Brothers in the late 1850’s – early 1860’s are the guys who showed Henry Comstock a lot of his methodology for getting things started,” said Burns. “We also learned they employed our very famous John Mackey and he learned a lot of his expertise from those Maldonado Brothers.”

According to Burns, the Maldonado brothers operated their mine traditionally, using a system known as el sistema del rato–the system of the moment. This mining system is sometimes referred to as “rathole” mining, an occasionally derogatory term which stems from an butchered translation of the Spanish language.

Using the patio process and el sistema del rato, the Maldonado’s Mexican Mine was one of the highest producing silver mines in the early years of the Comstock. However, eventual legal troubles and internal theft would force the Maldonados to sell the mine and leave the area.

“One of their employees stole a whole bunch of their ore, and they had to sell the mine,” said the Curator of the Latino Miners exhibit Mariah Mena.

However, the legacy of the Mexican Mine does not end with the Maldonados.

“Later in History, John Mackey buys a mine just north of where they were digging and he ended up naming it the Mexican Mine in honor of [the Maldonados] calling their mine the Mexican.” said Burns.

Where did they go, what don’t we know?

There is still much to be learned about what society was like for the Latinos living in Virginia City. One area of focus for von Nagy and his team were the Mexican social clubs that popped up across the country during the time of the Comstock. The mining boom was occurring at the same time as the Second French Intervention in Mexico, and Mexicans living in the United States created social clubs to support the resistance to French intervention. Evidence tying to the social club at Virginia City is one of the few clues relating to the size and social activities of the Latino population in the area.

“We know they had a major community center in what is now the Northern part of Virginia City, that would have been adjacent to the mine[…]Virginia city had one of the largest in the country,” said von Nagy.

“One document I found said there were 870 members just in the Virginia City-Silver City-Gold Hill region,” said Mena.

The existence of such a large social club suggests that the scope of the Latino population in the city is understated. The social clubs were hubs of promoting Mexican patriotism, and this fervor extended into holiday celebrations.

- Outdoor tourism businesses could take a financial hit as international travelers avoid Nevada

- Future of the Sierra Nevada Job Corps Still Unsure After Possible Final Graduation Ceremony

- Move Your Feet To Reno’s Latin Dance Scene

- The Highs and Lows of Latino/a/x representation in Netflix’s ‘Wednesday’

- How a UNR student fights cancer — and for her future

“Diary entries talk about Cinco de Mayo celebrations when [Mexico] defeated the French and Mexican Independence Day and there are stuff in the newspapers that talk about parades and that they participated in larger parades like Christmas parades,” said Mena.

However, vestiges of this past community are hard to come by, and contributes to their erasure from the story of the Comstock.

“A lot of people [when discussing the history of the region] would bring up the Hispanic population as if they did not have much contribution to the area and that is a huge misconception,” said Burns.

Of course, the Latino population in the town was not only involved in mining.

“The most surprising thing was the wide variety of jobs,” said Mena, “There was everything from mulepackers to ore prospectors, musicians, seamstresses, bar owners, just pretty much everything you could imagine these people were involved in.”

One of the major contributing factors to the lack of evidence of the Latino community in Virginia City was the great fire of 1875, which destroyed the Northern end of the town where the Latino community resided.

“There is this huge presence[…] the broader public doesn’t know about it and it is not something that is presented much in Nevada.” said von Nagy. “There is a building associated with the patriotic club, but it is not there anymore.”

The Shared History Program’s Latino Miner exhibit is available for public viewing in Lincoln hall. The exhibit features 25 panels and is presented in both English and Español with a focus on accessibility.

This article was written by Vincent Rendon and shared with Noticiero Móvil.