Addressing mental health challenges for Latino communities

July 21, 2023 By

Noticiero Movil

Editor’s note: This is the second installment of the KUNR series Mental Health in the Silver State. In the coming months, we’ll continue to explore how mental health impacts the lives of Nevadans.

Jaime Gonzalez-Aguirre started working when he was very young, either helping his immigrant father with a taco truck or mowing lawns. When it was time to go to college, Gonzalez-Aguirre kept working to pay his way through school. He graduated from UNR in May.

But the stress of school and work were taking a toll. And the DACA recipient was also fighting to become a permanent resident, increasing his stress level. In 2019, he knew he needed help, so he made an appointment with a therapist. But the therapist he went to was typical of what many Latinos encounter when they seek out a therapist.

“When I got [to] the appointment, she was Caucasian, blonde. And I was wanting to say ‘I really want to give it a try. I do need the help. I need to know that I can’t do everything by myself,’ ” Gonzalez-Aguirre said.

Despite trying, he didn’t feel understood.

“There was nothing that she could actually speak to personally. She was just letting me vent and said, ‘If you want to set up next time, we’re gonna do so,’ but I felt like it was going to be talking to a wall again. I needed someone that could understand the situation. So I never followed back up,” he said.

Feeling understood by a mental health professional is crucial to successful treatment, but that is not always possible, said Sandra Leon-Villa, a Las Vegas-based psychologist.

“What that means for folks who are seeking mental health services is that it’s very likely that you’re not going to necessarily be running into someone who looks like you,” said Leon-Villa.

This is a common situation for Latinos seeking help. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness or NAMI, Hispanic adults are 50% less likely to receive mental health treatment as compared to non-Hispanic whites.

And that is because Latinos face numerous obstacles when trying to access these services – including language barriers and stigma.

In many Latino families, mental health still remains a taboo. Some people do not seek treatment out of fear of being labeled as “locos” or bringing shame to their families.

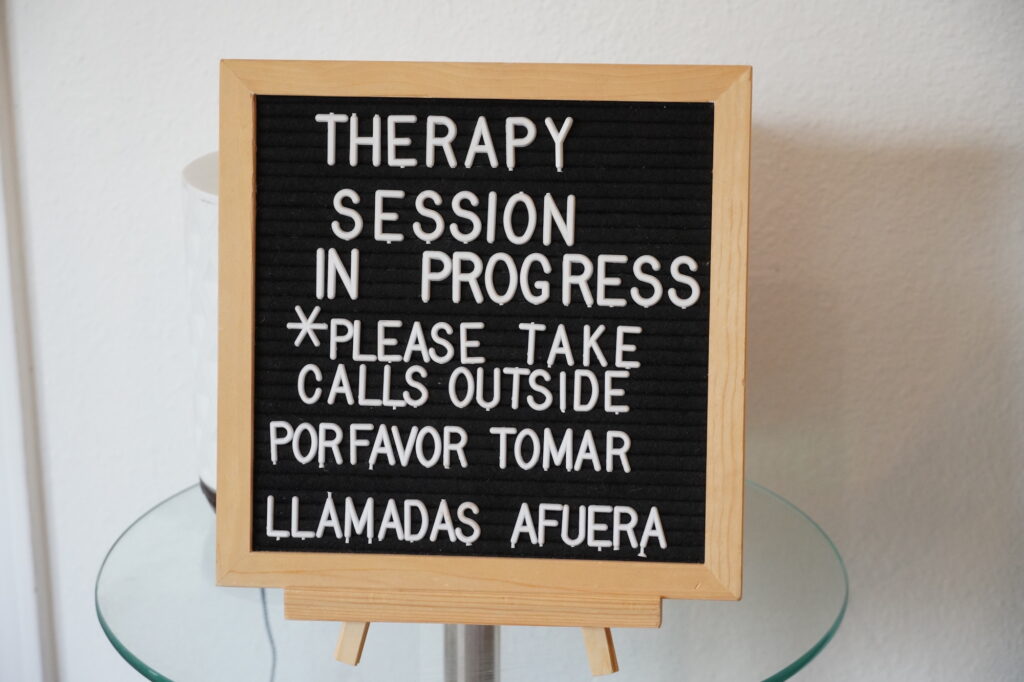

A person showing symptoms of depression is often seen as lazy by older Latino generations, said Leslie Bonilla, a therapist at Family Behavioral Health, one of the few fully bilingual providers in the Reno-Sparks area.

“I see that with adolescents when I work with like mom saying ‘pues es bien huevon, es perezoso,’ and I’m like, no, we need to really educate about what depression is. What does that look like? What does it mean to have it?” said Bonilla.

Other factors also play into Latinos getting help. According to NAMI, immigration status also affects Latinos’ access to mental health services. The fear of deportation can prevent undocumented immigrants from seeking help.

And lack of health insurance leaves Latinos with even fewer options. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 20% of Hispanics have no form of health insurance.

Lourdes Calzada-Santacruz, also a therapist at Family Behavioral Health, said that shouldn’t be a limitation because there are other options for the uninsured.

“A lot of times, therapists will find a meeting ground and offer something that can be helpful. If we look at our ethical codes, we should be able to provide some pro bono services,” Calzada-Santacruz said.

In addition to all these barriers, there is one more: The lack of cultural competence among mental health professionals.

According to NAMI, due to these cultural differences, mental health providers may misunderstand or misdiagnose Latino patients.

About 7% of licensed psychologists in the U.S. identify as Latino, according to the American Psychological Association.

For example, someone might describe what they are feeling with a phrase like “Me duele el corazón.” While this literally means “my heart hurts,” it is an expression of emotional distress — not a sign of chest pain.

A culturally sensitive professional would be aware of this interpretation and would ask for more information instead of assuming the problem is purely physical.

A provider without training on how culture influences a person’s interpretation of their symptoms is highly likely to misdiagnose them, according to NAMI.

Black and brown men and boys are more likely to be misdiagnosed, Leon-Villa said.

“They’re more likely to get diagnosed with a conduct problem, a behavioral disorder, or even a personality disorder. And a lot of that has to do with the fact that providers aren’t really trained in cultural nuances and cultural differences,” she said.

Another common value in the Latino community is “familismo,” a cultural foundation that emphasizes strong family bonds. Leon-Villa said it is common for Latinos to prefer family therapy.

“American culture really focuses on independence. And a lot of us, because we come from interconnected communities where we believe in extended families, when we have Latinx families that come into the office, oftentimes, they’re bringing in their entire family, even though we’re only seeing the one person,” Leon-Villa said.

Despite the lack of culturally competent mental health professionals in Nevada, some steps have been taken to improve the situation.

In June, Governor Lombardo signed a new Nevada law requiring psychologists, therapists and social workers to complete at least six hours of instruction relating to cultural competency and diversity, equity and inclusion.

In Northern Nevada, the National Hispanic Medical Association’s Nevada Chapter offers resources to the Latino community, such as “Acá Entre Nos,” bilingual meetings about mental health.

If an individual is unable to find a professional with whom he feels comfortable or represented, virtual counseling may be an option, Leon-Villa said.

“If we’re licensed in Nevada, we’re able to provide services in the entire state. And sometimes that might mean seeking telehealth services, which is just as effective as face-to-face therapy,” she said.

Although he tried going to therapy, it just didn’t work for Gonzalez-Aguirre. Instead, he relies on support from friends.

“When it comes to mental health, I just rely on my friends, the ones that know me close, the ones that have been through struggles the same as I have, and the ones that I’ve known the longest because those are the ones that are really gonna understand you,” Gonzalez-Aguirre said.

In August, KUNR’s Kaleb Roedel will report about mental health among farmers.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. Go to NAMINevada.org for a list of resources and other information.

This article, which was shared with Noticiero Móvil, was reported by María Palma of KUNR Public Radio originally published on July 19, 2023.