In the dichotomy of Latin American cinema, there are few entries that explore the aftermath of the Zoot Suit Riots in the 1940s. This was a series of violent clashes between young Latinos against U.S. servicemen and citizens, and this revolutionized the presence of Latinos in America and it also generated a unique identity for Mexican-Americans.

This identity is known as Chicano, which refers to people of Mexican descent born in the United States and who refuse an Anglo self-image. Prevalent in the 1970s on account of the Chicano Movement advocating for equal rights, it was reinforced in the 1990s when those born of freedom fighters continued the mission of their parents by defining their own style, artistry, and vernacular that was unique to them.

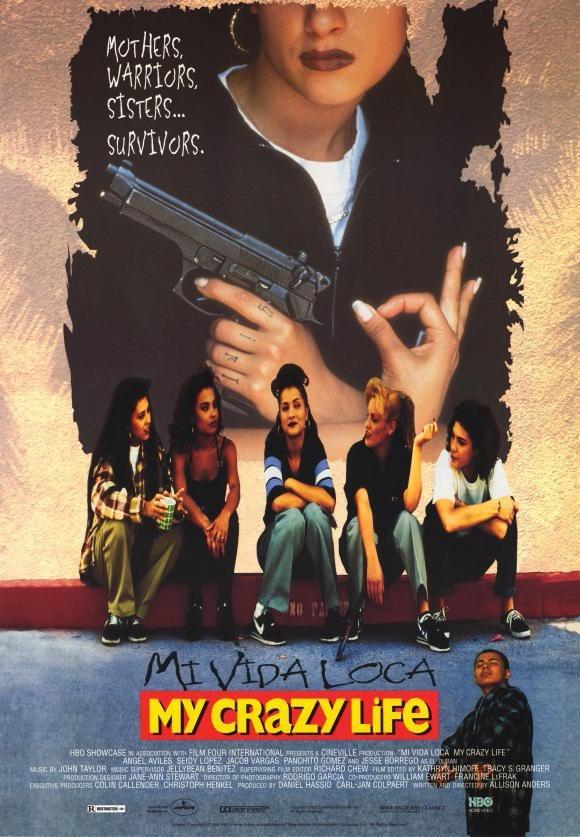

With this knowledge, there is one film that excellently encompasses the revolutionized culture of Chicanos: Mi Vida Loca.

Synopsis

Mi Vida Loca (Allison Anders, director, 1994) is a film that captures the elegance of 1990s Chicano culture, while also amplifying the brutality of gang violence.

In the film, there are several vignettes of different characters that encompass various aspects of being Chicano in Los Angeles and the need to join a gang to survive. From the rivalry and subsequent reconciliation of Sad Girl (Angel Aviles) and Mousie (Seidy López), the gender disparities between the locos and the locas, and the revitalization of love in the hood in contrast to other films of the 1990s.

Above all, Mi Vida Loca contests the various stereotypes of Latinos in film, especially those of machismo and the idea that women are weak. Moreover, Mi Vida Loca also rejuvenates the concept of family, especially when those in gangs lose their actual families and find warmth from the other people.

The film is a timeless depiction of Mexican Americans and the issues plaguing their communities, concluding with a sequence that highlights the heartbreak that results from gang violence.

The Presence of Women in Chicano Culture

One aspect of the film that acts as the foundation for the actions of the characters is the relationship between Mousie and Sad Girl.

The issue that arises between them takes form in Ernesto (Jacob Vargas), the boyfriend of Mousie and the father of their child. He cheats on Mousie with Sad Girl, and rather than blame Ernesto for his infidelity the two women blame one another and let a man infect their life-long friendship. Their hatred leads them to challenge one another to a duel, with the anticipation that one of them will die. A tragedy, but it is anticipated in these patriarchal communities.

Jose Isla/Flickr/CC BY-NC 2.0

Although not explicitly presented in the film, the locos have more of an influence than the locas and the latter bend knee to the whim of the men. This is precisely why Giggles (Marlo Marron) was sent to prison. She followed Creeper’s lead and this resulted in Creeper being killed and Giggles having to serve four years. Therefore, this provides an explanation as to why Mousie and Sad Girl were quick to threaten one another rather than Ernesto.

Nonetheless, it did not matter in the end because Ernesto’s machista behavior towards women resulted in his death. Specifically, he is killed by a female client that performed sexual favors for him in return for drugs. Ernesto is unfaithful to Mousie and unfaithful to Sad Girl, and he takes chauvinistic pride in having influence over white women too. While this does not justify his untimely death, it is clear that his overt masculinity was what provoked it.

Returning to Giggles, her presence acts as the clarity that the two women need. Giggle is a prime example of what happens when men are in control of their fate. This sets them both down the path of atonement, enacting their drive to want to give back to Echo Park by transforming Ernesto’s death into something that inspires change.

Boys Do Cry: How Mi Vida Loca Refutes Toxic Masculinity

With Ernesto’s death, the need to be strong in the face of death dissipates.

This is primarily shown through Sleepy’s (Gabriel Gonzales) breakdown to Big Sleepy (Julian Reyes) discussing loss within the community. For Latino men, there is an archaic notion that men do not cry or show emotion, because it is a sign of weakness and femininity. But, Mi Vida Loca highlights that this is not the case and Sleepy has every reason to mourn the death of Ernesto.

Big Sleepy is meant to be the apex of masculinity within the barrio, but throughout this sequence, he never tells Sleepy to withhold his emotions and to “be a man.” Big Sleepy also lost his best friend when he was 16, and to this, he stated, “You lose a part of who you are inside.” This line of dialogue strengthens the fact that sadness is not a weakness, especially when it is Big Sleepy saying it.

Jose Isla/Flickr/CC BY-NC 2.0

For the audience and characters in the film, it is a rebuttal to the motif that Latino men are meant to be headstrong at all times. Death is immense pain, and Big Sleepy can attest to this and relay the message of vulnerability being a virtue, but one must find strength in moving forward in life.

What’s more, Big Sleepy physically embraces Sleepy to comfort him and silently encourages him to express whatever he feels as he weeps. For context, Sleepy is both mourning the loss of Ernesto and feeling as though he did not do enough to save him. This tender moment between the two is unique because Big Sleepy is a father figure to him and seldom do you see sequences in Latin American cinema where two non-related men can have this sort of embrace.

Big Sleepy knows exactly what Sleepy is going through and encourages him to mourn because then Sleepy will have the autonomy to absolve himself and move forward. As presented, Giggles and Big Sleepy are from a more traditional Echo Park community, and yet it is apparent that they do not adhere to tired gender regulations present in their day. Women do not need to rely on a man to survive in the barrio, and men do not always need to be pillars of strength and are permitted to cry.

Romance en el Barrio

Mi Vida Loca is highly successful in exploring the nuances of love and the emotional aftermath. There is a myriad of films from the 1990s that are successful in showcasing the idea of familial love, platonic love, and romantic love. For example, Set it Off (F. Gary Gray, 1996) was successful in platonic love and intimate friendships, while Menace II Society (The Hughes Brothers, 1993) was more successful in familial love and selflessness.

But Mi Vida Loca encompasses the more visceral iterations of love.

There is a tightness between Mousie and Sad Girl that is unlike any other female friendship in film, and their reconciliation integrates the beauty of evolution. After all, only true friendships can survive the aftermath of a failed duel to death. Additionally, La Blue Eyes’ (Magali Alvarado) relationship with Juan Temido i.e. El Duran (Jesse Borrego) while he was incarcerated is a type of romance rarely depicted in films. There is an intimate connection that arises when one’s means of communication is solely writing. This is why La Blue Eyes refused to experience that heartbreak that results from never hearing back from someone you’ve fallen in love with. She is blinded by the concept of unrequited love, resulting in her constantly writing and awaiting a response.

Mi Vida Loca is revolutionary in presenting a romantic endeavor that is rarely presented in Latin American cinema, let alone cinema as a whole.

The Importance of Loss in the Film

Through it all, however, there is one particular sequence that captures the overarching concern of gang violence: the loss of innocence.

To preface, El Duran is presumed to have stolen Ernesto’s truck, dubbed Suavecito, and the locos intend to take vengeance at a dance in River Valley. La Blue Eyes experiences heartbreak upon realizing El Duran is a womanizer, and the locas leave the dance to comfort her. Meanwhile, the locos arrive at the venue, and with the others distracting the guard, Sleepy shoots El Duran and he dies. But, it is revealed that El Duran never took the truck and one of the neighborhood boys took Suavecito for a joy ride, meaning he died for nothing.

At first, the film ends on a presumed positive note, until a truck rolls up on Sleepy and Big Sleepy’s daughter. One of El Duran’s women aims to get payback for his death and she pulls a gun out on Sleepy, and claims, “This is for El Duran.” With that it appears that Sleepy will be another victim of gang violence. However, once the camera pans out and reveals the scene, it turns out she missed and shot Big Sleepy’s daughter instead. Big Sleepy is utterly devastated, and the film ends with her funeral and all of the characters paying their respects.

Inarguably, this is the perfect ending to the film because it exhibits the true loss of innocence. The daughter had her entire life ahead of her, and she was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. This statement is the pinnacle of gang violence in Echo Park because most of the time, there are more innocent casualties than intended victims. The woman wanted to shoot Sleepy, but she shot a little girl instead.

Mi Vida Loca demonstrates the life of Chicanos in Echo Park, but also criticizes the gang hierarchies that do more harm than good. There is a sense of belonging and family in the gang, where older members can act as parental figures, specifically Big Sleepy. But, the reality is that it is not a pious life and someone you love will eventually fall victim to the violence.

Angel Garcia, who graduated in December 2022 from the University of Nevada, Reno with an English degree, contributed this article to Noticiero Móvil.

This commentary is part of the “Latinos in the Eyes of the Media” special series. In this section, Noticiero Móvil publishes pieces by UNR students that dive into films and television shows in which Latino characters, culture and norms are portrayed. The goal is to explore and illuminate how a lack of Latino representation in the media continues to promote some of the discriminatory and stereotypical practices that affect Latinos to this day in the U.S.